A powerful and moving film that doesn’t make overt commentary or judgment on the differing faiths, but nevertheless touches on the deeply profound differences and similarities shared by all humans in times of great crisis.

Cinema provides such fertile ground for the dramas and crises that arise from the idea of faith. While it is difficult, and perhaps even possible, to distill the complex socio-economic-political reasons behind warring states and clashes over religion in various parts of the world, film has always provided a microcosm to explore the subtleties of global movements in a way that broadcast news never could hope to achieve.

Cinema provides such fertile ground for the dramas and crises that arise from the idea of faith. While it is difficult, and perhaps even possible, to distill the complex socio-economic-political reasons behind warring states and clashes over religion in various parts of the world, film has always provided a microcosm to explore the subtleties of global movements in a way that broadcast news never could hope to achieve.

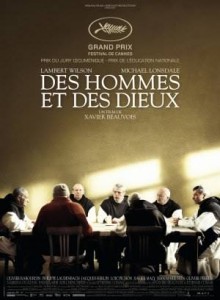

Of Gods and Men (Des hommes et des dieux) received the Grand Prix and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, with the latter award created by Christian members of the film community to “honour works of artistic quality which witnesses to the power of film to reveal the mysterious depths of human beings through what concerns them, their hurts and failings as well as their hopes.” While it could be argued this tag applies to almost every great film in history, there is something overwhelmingly powerful about the exploration of faith in Xavier Beauvois’ film.

In 1996, seven French Trappist monks were kidnapped from the monastery of Tibhirine in Algeria and were later found beheaded. Although the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria claimed responsibility, the identity of the killers remains a topic of some debate. In the film, we meet eight monks, led by Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson, The Princess of Montpensier), who live in harmony with their nearby Muslim brothers. When some foreign workers are massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, terror grips the region. Refusing the army’s help, the monks resolve to stay and face whatever trouble may come their way.

Of Gods and Men often seems to present a simple dichotomy to audiences, offering a clear distinction between the serene and harmonious monks and the rebellious and murderous Islamic fundamentalists. Yet the situation, as the monk’s non-attempts to convert the nearby Muslims would indicate, is far more complex than that. This year, the Alliance Française French Film Festival has reminded us of France’s past crimes in the occupation of Algeria through the psychological thriller A View of Love and the explosive drama Outside the Law. Of Gods and Men fleetingly acknowledges this occupation of Algeria, with the passing suggestion that the French presence in Algeria after years of war crimes is deliberately antagonist. Yet the monks are none of these things. They are French, but they exist in an austere bubble and the film chooses to concentrate on the strength of the monk’s will rather than what they may represent to the surrounding world.

Surrounded in a world of meditative musical chanting, the performances are impeccable. The always reliable Lambert Wilson gives another strong turn as the ‘leader’ of the group, providing the pillar upon which the other monks’ will rests. Similarly, Agora‘s Michael Lonsdale provides A particularly moving scene come during a dinner sequence, where Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake” plays and momentarily breaks us (and the monks) out of the cloistered world we have been inhabiting with the monks for a surprisingly breezy 122 minutes of contemplative filmmaking.

Of Gods and Men played in Australia as part of the Alliance Française French Film Festival. It will be released in Australia on 26 May 2011 from Sony Pictures Entertainment.

No Responses