It is fair to say that Hong Sang-soo is a filmmaker who defies the conventions of traditional audience-driven cinema. Hong reached the heights of his international acclaim in the last year following the success of Hahaha, winning the Prix Un Certain Regard at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival over Derek Cianfrance, Xavier Dolan and Jean-Luc Godard.

It is fair to say that Hong Sang-soo is a filmmaker who defies the conventions of traditional audience-driven cinema. Hong reached the heights of his international acclaim in the last year following the success of Hahaha, winning the Prix Un Certain Regard at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival over Derek Cianfrance, Xavier Dolan and Jean-Luc Godard.

In the face of a market that demands the increasingly action-packed, dramatic and stylish horror-filled cinema that South Korea is rapidly developing a reputation for, Hong Sang-soo’s cinema is a contemplative one, eschewing the beatification of national monuments for the examination of the details of the every day.

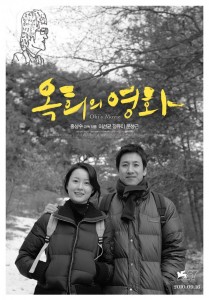

Ostensibly, Oki’s Movie (옥희의 영화) is about Oki (Yung Yu-mi, A Million) making a short film at college. Her friend Jingu (Lee Sun-kyun, Officer of the Year) expresses his feelings for her, not knowing that she is secretly romantically involved with Professor Song (Moon Sung-keun, Visitors). Dealing with three separate but interacting characters, Oki’s Movie is split into four sections, each framed within the conceit of being a student film made in amateur fashion.

With Oki’s Movie, much like other films from Hong, there is an element of autobiographical self-reflection to the narrative, steeped in the master-apprentice world of filmmakers and film students. Opening with rough, amateurish credits (complete with Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” blaring over the speakers) that are also used as a framing technique for the four segments, this film has many of Hong’s signature touches. The comedic moments are all there, especially in a hilarious opening section in which a drunken Jingu downs a bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue, at least to start with, and proceeds to tell Song exactly what he thinks.

Yet in an uncharacteristic move, the film is told from the perspective of a woman, as the title would imply. This makes the awkwardly intimate moments in which Jingu professes his love, or the strange relationship between Song and Jingu, all the more comical. Audiences may have difficulty accessing this world due to its rough frankness, but once you go with it, it is far more rewarding than the manufactured relationships of its Hollywood brethren.

The strongest of the segments, aside from Jingu’s opening gambit, is the final section narrated by Oki. Here Hong, by way of Oki’s titular movie, juxtaposes Oki’s separate walks in the park with her two suitors. Here Hong is at his best, delivering an intensely personal study tied to a specific time and place, finding the moments of humour and intimacy in the simple act of taking the same walk with two different men: the older man and the younger man. There is an almost fairytale-realism to the sequence, and that dichotomy is where the magic of Oki’s Movie lies.

Oki’s Movie screened at the Melbourne International Film Festival. It will also screen at the Korean Film Festival in Australia (KOFFIA) on 29 August 2011 in Sydney.