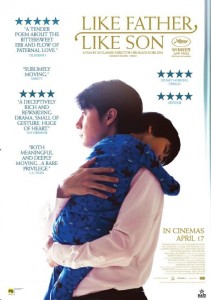

Hirokazu Koreeda continues his exploration about family and culture in Japan, crafting a deliberately paced drama out of the simplest of moments.

Director: Hirokazu Koreeda

Writers: Hirokazu Koreeda

Runtime: 120 minutes

Starring: Masaharu Fukuyama, Machiko Ono, Yoko Maki, Lily Franky, Keita Ninomiya, Shogen Hwang, Isao Natsuyagi, Kirin Kiki

Distributor: Rialto (Australia)

Country: Japan

Rating: Highly Recommended (★★★★½)

Throughout his career, the works of Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Koreeda have been characterised by his exploration of family, and the changing nature of the traditional Japanese family unit. Grounded by his roots in documentary, it has often been said that Koreeda’s observational approach recalls the works of master Yasujiro Ozu. Indeed, had Ozu been making films today, his eye would have undoubtedly fallen on some of the same places that Koreeda has spied. With Like Father, Like Son (そして父になる), Koreeda questions whether it is blood or proximity that forms those lasting ties.

Ryota (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a successful Tokyo architect, emotionally putting his wife Midori (Machiko Ono) and six-year-old son to one side as he strives for perfection. They are shocked to receive a call from the hospital where Keita was born, informing them that their son was switched at birth with the child of Yudai (Lily Franky) and Yukari (Yoko Maki). Over the coming months, both couples must decide whether to keep the child they have known for the last six years, or to reunite with their biological children.

In Koreeda’s previous film, I Wish, he focused his attention on the world of children, and in Like Father, Like Son, he shifts his lens back to the interrelationships between fathers and their sons. Koreeda sets up a simple dichotomy between the two families, with Ryota’s success-driven unit diametrically opposed to Yudai’s large communal unit, living and working out of a repair shop in suburban Tokyo. Yet Koreeda never comments on which might be the “better” of the two models of family, simply observing that they are different, and allowing the audience to draw its own conclusions as to who the children rightfully belong with. The real beauty of the film is that thoughts and opinions shift rapidly as the narrative progresses, and Koreeda creates tension and momentum out of the gently-placed duck blind that he has seemingly set up just out of sight of the film’s frame.

Musician and actor Fukuyama makes a compelling leading man, and his restraint makes us uncertain as to whether he is keeping his emotions in check, or being far more calculating in his decisions. When he eventually breaks, we watch as he comes to grips with the difficult relationship he has with his own father (veteran Isao Natsuyagi in a wonderfully scene-stealing role) and the realisation that his absent nature has gone towards creating a similar pattern in his own ‘son’. Franky’s almost lackadaisical character is initially presented as being preoccupied with compensation, although his homespun wisdom belies a benign cluelessness that can’t help but make him an instantly likeable fellow.

Despite the male-centric title, the film is also just as much about the impact on women in Japanese families, underscored by this very marginalisation. Off to one side, some of the most telling moments include Yukari’s confession to Midori that some of her crueller friends had suggested that she must have had an affair for her child to look so different. Familiar face Kirin Kiki, an almost essential ingredient in Koreeda’s oeuvre, delivers a down-home gracefulness to Midori’s mother, who has a similarly complicated relationship with her daughter. In fact, there’s probably a parallel film to be told just about the women in here as well.

Nobody quite makes films the same way as Koreeda, here somehow combining a very contemporary story with a traditional form of storytelling around a topic that hasn’t realistically been an issue in Japan since the 1960s. Yet the themes are universal, and while you may question the notion of nature versus nurture as the film progresses, you can rest assured that Koreeda is subtly guiding you along that journey the whole way.

Like Father, Like Son is released in Australia on 17 April 2014 from Rialto Distribution.