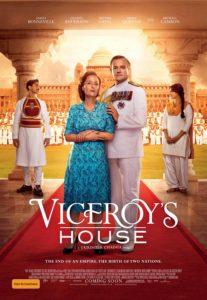

The British don’t have a great track record when it comes to exiting places. While their most recent withdrawal remains in headlines around the globe, their 1947 departure from India is arguably the most notorious. The exit strategy left the nation partitioned into India and Pakistan, based on Hindu or Muslim majorities, displacing an estimated 15 million people, including 2 million people said to have died in the upheaval. In VICEROY’S HOUSE, filmmaker Gurinder Chadha (Bend It Like Beckham) focuses on the common people in the story, but in doing so misses the bigger picture entirely.

For 300 years, the Viceroy’s House in Delhi served as the home of British rule in India. Following the Second World War, and the efforts of Ghandi, the Empire could no longer afford to maintain a position there. Lord Mountbatten, great grandson of Queen Victoria, is sent to India with his wife Edwina (Gillian Anderson) and daughter to be the last Viceroy and shepherd an independence. However, the divisive factions in the country force a compromise that bears the Mountbatten name and splits a country apart. Against this backdrop, house workers Jeet (Manish Dayal) and Aalia (Huma Qureshi) fall in love despite their religious differences.

In the tone-deaf approach to this historical nexus, the Mountbatten’s are bizarrely depicted as blameless victims. Informed by Narendra Singh Sarila’s book The Shadow of the Great Game, Winston Churchill is the preordained villain, and the outcome a fait accompli. Completely ignoring Lady Edwina’s affair with Prime Minister Nehru of India, Anderson’s character is more attracted to the quirks of the country, casting her as a social justice champion. She even sends one staff member home to Britain for being racist. Of course, this is perhaps a 20-20 revisionist view based on her almost universally praised relief efforts during the displacement.

If Chadha’s unique viewpoint is the Upstairs, Downstairs of Indian history, then it’s a shame that the secondary story is filled with overwrought drama. Ticking off boxes that skirt very close to a dance-off fight between Hindu and Muslim citizens, and a climax that literally has our star-crossed lovers calling each others names across a crowded marketplace, Chadha and her co-writers (Paul Mayeda and Berges Moira Buffini) don’t tell the story from ground-up so much as they bring it crashing down to the basest level.

The film is lovingly shot by Ben Smithard, with glorious views of the country. AR Rahman’s ever-present score is like a lightweight Howard Shore. The supporting cast is peppered with the likes of Michael Gambon and Simon Callow, but Neeraj Kabi somehow gets Mohandas Gandhi completely wrong. At least he fairs better than Pamela Mountbatten (Lily Travers), who doesn’t get much more to say than a certain Monty Python character in her perfunctory appearance.

The film’s coda speaks of Chadha’s grandmother being one of the survivors of the great exodus, and there’s clearly some personal stakes at the heart of VICEROY’S HOUSE. It’s disappointing that her melodramatic approach misses political nuance and exchanges it for superficial relationships.