In The Evolution of the Western – Part 1: The Last Gunslingers, we discussed the changing nature of the cowboy over the first half of the 20th century. From the earliest days of cinema through to John Ford’s The Searchers (1954), the gunslinger turned from hero of legend to “a figure of pathos, not tragedy” and in films such as Shane, the “disturbing revelation of the savagery that prevailed in the hearts of the old gunfighters, who were simply legal killers under the frontier code”. Yet the tin star was fading in the Hollywood limelight by the beginning of the 1960s, in favour of more realistic and gritty depictions of human violence.

In The Evolution of the Western – Part 1: The Last Gunslingers, we discussed the changing nature of the cowboy over the first half of the 20th century. From the earliest days of cinema through to John Ford’s The Searchers (1954), the gunslinger turned from hero of legend to “a figure of pathos, not tragedy” and in films such as Shane, the “disturbing revelation of the savagery that prevailed in the hearts of the old gunfighters, who were simply legal killers under the frontier code”. Yet the tin star was fading in the Hollywood limelight by the beginning of the 1960s, in favour of more realistic and gritty depictions of human violence.

This three-part series explores just how much that contribution has changed over the years, and how it has influenced and been influenced by other films around the world. In this part, we’ll take a look at the turning of the tide as filmmakers rebel against not only the old world ways of telling a story, but in the very values of the United States. Europeans begin to spin their own version of the western myth as it is revised, and gets a little bloodier. We also take a journey into the surreal and the Man With No Name drifts into town.

A new dawn

We we last saw our gunslinging heroes, the sun was setting on them as they rode off towards it. Yet the traditional western hero wasn’t going to go down without getting a few shots off. 1960 kicked off with a the star-studded western The Magnificent Seven, directly influenced by Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai. The influence of Kurosawa would be vital to the western in the 1960s, in much the same way that the Japanese master was influenced by John Ford’s westerns in his own works. Indeed, Trifonova refers to the “intertextual relationship between Westerns and Japanese samurai films”. After more than half a decade of defining an all-American genre, the rest of the world was starting to show their love for the genre, and show the US how it was done in the process.

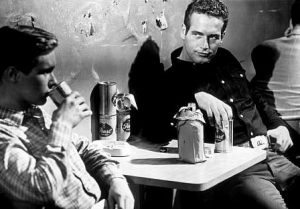

The early 1960s saw the genre trying to establish itself in the new dawn of filmmaking, where the Hollywood studio fare was losing favour with the public. The Alamo (1960), produced, directed by and starring John Wayne (as who else but Davy Crockett?), was an incredibly expensive (approximately $12 million) and long (202 minutes in the roadshow cut, eventually trimmed to 167 minutes) film met with mixed critical and box-office response. Contemporary westerns began to make more of an impact, also indicating changing audience tastes, with The Misfits (1961) from the legendary John Huston and Martin Ritt’s Hud (1963) starring Paul Newman being stand-outs of the era. The latter foreshadowed the cynicism that was creeping into not only westerns, but many popular Hollywood films made for an audience embittered by war and McCarthyism. Newman’s Hud expresses it best: “You take the sinners away from the saints, you’re lucky to end up with Abraham Lincoln”.

Marlo Brando’s directorial debut, One-Eyed Jacks (1961), not only proved that the star of films such as On the Waterfront and A Streetcar Named Desire could act, he was also a fine helmsman. It was significant for other reasons too, as marked another turning point for the direction of the western genre. Garrett Chaffin-Quiray notes it was “important in connecting Western classics of the 1950s with genre experimentation of the 1970s” (2005, p.395). Unfortunately for the film world, it was Brando’s only effort behind the camera. How the West Was Won (1962) – utilising the directing talents of John Ford, Henry Hathaway, George Marshall and an uncredited Richard Thorpe (last ‘epic’ western?) – is one of the last great epic westerns. Split into five segments, it was one of the few films shot using the three-strip Cinerama process, and was projected using three synchronized 35 mm projectors onto a large screen more deeply-curved than other formats. The expensive process meant it was rarely used for features of this kind, not least of which because its 2.89:1 aspect ratio meant difficulties in reformatting it for more traditional screens.

Yet the early 1960s saw a mad scramble to try and identify the western with a more modern and sophisticated audience. There were a stack of B-westerns in this period, typically starring someone like war-hero-turned-actor Audie Murphy, complete with titles along the lines of Seven Ways from Sundown (1960), The Broken Land (1962) and Posse from Hell (1961). An exception in this period is John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), starring both John Wayne and James Stewart. Sergio Leone, who will be discussed in the next section in greater detail, described it as his favourite John Ford film because “it was the only film where he (Ford) learned about something called pessimism.” Leone was certainly influenced by these pictures in the making of his series of Spaghetti westerns, with the long duster coats definitely inspired by Ford’s late masterpiece. Yet audiences were searching for a new kind of hero, one that shared their cynicism and more cavalier attitudes to heroism.

Uomo senza nome: The Man with No Name

In 1964, everything changed. Italian director Sergio Leone released A Fistful of Dollars, based on Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. The first of a loose trilogy of films from the director to star Clint Eastwood, then virtually unknown internationally beyond his word in the TV show Rawhide, it launched the actor into the stratosphere. While it was not the first so-called Spaghetti Western, with that honour going to Michael Carreras’ Tierra brutal a.k.a Savage Guns (1961), it was certainly the most influential. Yet, as noted film scholar Sir Christopher Frayling (1981, p.121) notes that upon release the films “were almost invariably panned by reviewers” because the Italian films had “no ‘cultural roots’ in American history or folklore, they were likely to be cheap, opportunistic imitations”. By the time For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, The Bad & The Ugly (1966) were released – along with Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966) – audiences knew exactly what they were getting into and the slick editing, iconic costumes and extreme close-ups were like nothing being done in the US. Eastwood was a new kind of hero, no in it for the honour or glory, but for the money. He was a cynical hero for a jaded audience. Just the ticket.

On the Blu-ray supplements to the 2010 release of A Fistful of Dollars, Frayling enthusiastically states “Sergio Leone not only reinvented the Italian western…he reinvented the western as well, and in the process re-energised a genre that had run out of steam, not just in Italy but in America as well”. In the same year as A Fistful of Dollars, Martin Ritt adapted The Outrage (also from a Kurosawa film, Rashomon). By way of comparison, its contemporary major studio efforts like Universal’s Bullet for a Badman (1964), another Audie Murphy B-western, seemed antiquated by comparison. In striking contrast to Leone’s punchy opening and score, R.G. Springsteen – a veteran of around 100 film and television western outings – played it very safe in the Universal backlot. A Fistful of Dollars, on the other hand, used Spanish and Italian vistas to full effect in Leone’s widescreen film that punch audiences in the face with its uniqueness.

The traditional western kept alive through The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), several sequels to The Magnificent Seven (The Return of the Seven (1966), The Guns of the Magnificent Seven (1969), and continued on int the 1970s with The Magnificent Seven Ride (1972)). Yet perhaps the crowning achievement of the Spaghetti western movement in the decade was Leone’s Once Upon A Time in the West (1968), the western to end all westerns! Showing “little concern for the Western’s traditional code…Leone’s version of the West is total anarchy with scarcely any room for heroism” (Frayling, 1981, p.281). Casting Henry Fonda as the villain was a masterstroke, his trademark piercing blue eyes not working against the character as one might expect, but cutting through his lackeys and viewers alike. Duck, You Sucker! (1971), also known as A Fistful of Dynamite, would be Leone’s final fully credited western – aside from some involvement with My Name is Nobody (1973) and A Genius, Two Partners and a Dupe (1975) and he would not get back behind the camera for almost 15 years for the gangster epic Once Upon a Time in America (1984).

Stop, Drop, Revise

After the cancellation of his TV series The Westerners, director Sam Peckinpah made his directorial debut with The Deadly Companions (1961), and followed it with the critically successful (at least in Europe) Ride the High Country (1962). Yet 1969 was another one of those turning points, with Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch aiming to put the nail in the coffin of the western forever. Bloody and violent, and set at the very bitter end of the frontier period in 1913, the film is just as much about the death western as it is about the death of the cowboy. A similarly bloody end came to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and True Grit (currently seen in remake mode from the Coen Brothers) gave John Wayne a late career boost with his Golden Globe winning performance as the eye-patch wearing Rooster Cogburn, a role he would reprise for one of his last on-screen performances in Rooster Cogburn (1975). The less said about Paint Your Wagon (1969) the better, but as a response to these more hard-hitting westerns, it was a sign that Hollywood was completely out of touch with the kinds of heroes that would appeal to audiences.

The 1970s still saw a number of westerns, but they were declining in influence and their traditionalism. Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970), a surrealist ‘Acid Western’, influenced everyone from David Lynch, through John Lennon to The Mighty Boosh. Peckinpah’s Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973) and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), a noir western, peppered the decade. Robert Altman’s less conventional McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971) joined Don Siegal’s Two Mules For Sister Sara (1970), with Clint Eastwood, the sci-fi Westworld (1973), Australia’s Mad Dog Morgan (1976), the revisionist The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976, Clint Eastwood), Elliot Silverstein’s A Man Called Horse (1970), the kiddie-comedy The Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again (1979) and the Robert Aldrich comedy The Frisco Kid (1979). On the small screen, Alias Smith & Jones entertained audiences, but generally it was a confused and uncertain decade for the western and its heroes, having broken free of the pre-1950s archetypes, but not entirely understanding their place in the second half of the 20th century.

Heaven’s Gate (1980) began the Decade of Shame with a gigantic flop and the expensive almost single-handed killed not only the western, but the large and unchecked budgets that maverick directors like Francis Ford Coppola and William Friedkin in the 1970s. Indeed, with the exception of Fred Schepisi’s Barbarosa (1982), Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider (1985) – essentially a revisionist version of Shane – Silverado (1985), very few serious westerns were made during the decade. Lighthearted fodder such as ¡Three Amigos! (1986) and the slick but fun Young Guns (1988) were the only things keeping the genre alive at the box office. Indeed, it was really only on television that more traditional westerns could be found. Lonesome Dove (1989), a mini-series based on Larry McMurty’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name, was an accurate and epic piece that did much to restore the image of the western in the public eye. Meanwhile, Little House on the Prairie – which had been running since 1974 – ended its run in 1982.

Was the western finally dead and buried, or was it ready to saddle up for a new adventure? The latter would prove to be true, but it wasn’t until the genre (and America) could examine itself from the inside-out that a new kind of western hero would emerge.

Final shots

In the next and final part of this series, we’ll take a look at the revival of the western beginning with Dances with Wolves and going through to today. We also ask the question: “When is a western not a western?”

Richard is the Editor in Chief of DVD Bits and The Reel Bits.

References:

Chaffin-Quiray, G. (2005) One-Eyed Jacks (1961). In S.J. Schneider (Ed). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. (Revised Edition, p.195). Sydney: ABC Books.

Frayling, C. (1981) Spaghetti Westerns. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

No Responses