Takashi Miike continues to put his own stamp on the jidaigeki genre, switching his penchant for bloodbaths to a serene examination of samurai honour.

Director: Takashi Miike

Writers: Kikumi Yamagishi

Runtime: 126 minutes

Starring: Ebizô Ichikawa, Hikari Mitsushima, Eita, Koji Yakusho

Festival: Sydney Film Festival 2012

Distributor: Icon

Country: Japan

Rating (?): Highly Recommended

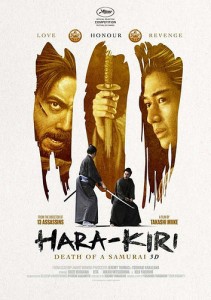

Maverick filmmaker Takashi Miike is now well over 50 films into his two decade career, and is showing now signs of slowing down. Indeed, with 13 Assassins, Miike was given another international lease on life, with genre fans rediscovering someone who has previously been known for the violent excesses of Audition and Ichi the Killer. Following that 2010 film, not without its own magnificently staged blood-letting, Miike began a short run of works which we could rightly call his jidaigeki films, which roughly translates as period dramas. The over-the-top comedy and fantasy elements of Ninja Kids!!! notwithstanding, Miike’s newfound fascination with the past has culminated in the uncharacteristically reflective Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai.

Based on Takiguchi Yasuhiko’s novel, Miike’s film roughly follows the same narrative of its first adaptation, Masaki Kobayashi’s Cannes award-winning Hara-Kiri (Seppuku) (1962). Where that film set out to critique Japanese militarism, Miike’s version is more about the conflict between honour and personal belief. Hanshiro (Ebizô Ichikawa), a poverty-stricken samurai, arrives at the House of Ii requesting the honour of committing seppuku (ritual suicide). Run by Kageyu (Koji Yakusho), who believes Hanshiro is bluffing to gain sympathy and employment, he is told the tale of Motome (Eita), who did just that months prior. Hanshiro’s final request sparks a drama filled with revenge and obligation.

Following 13 Assassins is a difficult task, and those expecting Miike to turn it exceed his signature levels of evisceration will be disappointed. Almost the antithesis to his previous works, Miike looks for a serene and natural beauty in every scene, be it snow falling on a courtyard or the unconscionable act of forcing a ritual suicide with a wooden sword. Even this scene, for all of its knuckle-whitening grimness, is Miike at his most restrained. The film sits in stark contrast to the stylised kabuki inspired pieces that usually typify jidaigeki, with drama originating not from loud proclamations, but slow-building tension and flashbacks. As we learn more about the motivations of both Motome and Hanshiro, and the connections between the two, the tension comes not from cruel torture but from a need to see justice fulfilled.

It is perhaps not without a sense of irony that Miike’s least frenetic film is the first to make use of 3D, although this too is used in a manner so understated that it is barely noticeable. Short of the title sequences and the snowfall, Miike and regular cinematographer Nobuyasu Kita simply use the format as a means to provide realistic depth to scenes that have little movement, perhaps indicative that the ubiquitous technology has already reached the limits of its natural lifecycle. Actor-composer Ryûichi Sakamoto‘s (Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) score adds to the subtle melancholy of Miike’s work. It is possible that after over two decades in the business, Miike has found the subtle groove he was destined for.

Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai played at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2012. It is released in Australia from 18 October 2012 from Icon.